Teaching Python to Biology Undergraduates

Last spring, I was asked to take over the "programming for life sciences" course for year 3 biology undergraduates at my university. I was reluctant at first, given the amount of work required to create material for an entire module, but something prompted me to take on this challenge. That "something" was a general interest in how to teach programming, particularly outside the software development field.

This is such an interesting challenge, and even more so in the current time, when everything is changing so rapidly with AI. I also felt that this was an essential part of the curriculum that we need to take more seriously. For our students to thrive in the future, being comfortable with computational approaches and having the appropriate tools to support algorithmic thinking and working with complex data are essential. I decided to accept based on my interest in the subject and my conviction that I would be doing something worthwhile.

To get started, I considered the following three questions: Why should biology undergraduates become proficient in programming? What should I actually teach them? How should I go about passing on knowledge and skills in this domain? This article summarises those reflections, drawing on the hindsight of having just completed the first cohort this autumn term. Below, I will walk through how I approached each of these questions and what I learned in the process.

Key Takeaways

- Python over R — Better positioned for AI/ML and teaches transferable OOP concepts

- Real data matters — DepMap gene dependency data engaged students more than toy examples

- Browser-first works — Pyodide and Colab remove setup friction; only 5/60 students adopted local dev

- AI changes assessment — Students reached further with ChatGPT, but measuring true understanding is harder

- The trade-off — "Innovation Tax" (2.3/4 teaching score) vs "Innovation Dividend" (3.4/4 practical skills)

- Next iteration — Slower pace (8 lectures not 5), mandatory local development, small invigilated exam

- Course materials — All resources available at Python for Biologists

Why teaching programming to biology undergraduates matters

I always liked working with computers, but as a biochemistry graduate student, it never occurred to me to dive into writing code. This seemed too far removed and a special domain better left to bioinformatics specialists with a foundation in computer science. There was also little necessity to learn programming skills. The data we handled consisted mostly of Western blots, microscopy images, some sequence analysis, and crystal structures; nothing that Excel, ImageJ, and other specialised desktop applications could not handle.

How things have changed! Biologists are now confronted with an avalanche of data: genomic, proteomic, high-throughput screening, alpha-fold structures, and high-content 4D imaging data, to name but a few in my specific area. Most of my colleagues are still hanging on to using specialised applications and data analysis tools rather than writing code themselves. I was, too, until I was encouraged to learn Python by a graduate student with a background in computer science. I used the downtime during the pandemic to teach myself the fundamentals and learn to work with larger datasets, such as DepMap, TCGA, and high-content microscopy screens. What I realised, then, is that coding allows you to experiment with data, pose new questions, and formulate new hypotheses. It quickly moves beyond simple data analysis and the generation of neat figures; instead, it empowers you to have a conversation with your data.

But does it still make sense to teach coding when AI can replace experienced software engineers and data analysts? I would argue that it makes a lot of sense, especially given the opportunities AI-assisted programming creates! It's true, one can vibe code a game, a website or give ChatGPT an Excel file and tell it in natural language what kind of analysis to do. But to really harness this power effectively and use AI to its full potential, basic coding skills make a big difference. To put it with Jensen Huang, the CEO of Nvidia: "You will not lose your job to AI, but you will lose your job to someone who uses AI". And those who know how to use AI effectively are generally good at coding and have specialised knowledge in other domains. Nobody knows what the job market will look like in 5-10 years. But I bet that having basic coding and even DevOps skills will be expected of most scientists and will make a difference when applying for jobs.

What to teach biology undergraduate students to become proficient programmers

Python or R

The choice of programming language is relatively simple: Python or R. Among our graduate students, it's roughly 50/50, with little crossover. I'm thoroughly biased towards Python, and here's why: for bioinformatics and data analysis, Python is fully equal to R. But Python offers something more as the core language for AI and machine learning, which increasingly shapes how biologists work with data. That makes it a better entry point for students who want to future-proof their skills. In my opinion, Python is also better suited to teach core concepts such as object-oriented programming. Lastly, Python's vibrant open-source ecosystem opens doors to areas beyond traditional data science, including web development, electronics, and image processing, to name but a few.

The next question is: how much Python do biologists need to know to begin doing something valuable and interesting? This is where it gets tricky! The two main areas where Python becomes useful quickly in biology are DNA analysis and work with large data frames, including statistics and visualisation. My plan was to spend about a month on basic programming concepts like basic control flow, code organisation, string manipulation and then move quickly to the most useful data science packages. This worked out quite well, although the first few lectures and practice examples were overloaded and challenging for complete beginners. I also made sure to include a brief section on classes and object-oriented programming. When I started with Python, I missed out on OOP completely, and this lack of basic understanding of class methods and attributes led to many struggles dealing with APIs of libraries such as pandas or matplotlib. I used Steve Jobs' hotel reception metaphor to convey the idea that complex systems should have a simple front-desk interface and explain why we package code into objects with simple APIs. I also demonstrated a Python class in action using a DNA object with a gene and species name attribute and a GC content calculation method. I think this worked well and the students understood immediately what happens under the hood when you say df.mean(), for example.

Biology has a major advantage in teaching coding concepts: interesting data sets are readily available and there is plenty of space for small scripts that are immediately useful to automate calculations in the lab. This helps a lot with keeping the material practical and suggests immediate application. Especially, projects with DNA analysis lend themselves to convey basic coding algorithms like search, iteration and translation. DNA is code after all so applying code for its analysis makes immediate sense.

Data science

After teaching the coding basics using the Python standard library I moved quickly to the most commonly used data analysis and visualisation libraries. Working with large tabular datasets and visualising quantitative relationships of data is probably the most common use case for Python in the biosciences. The brief OOP interlude I described above helped a lot here and my impression was that the students quickly grasped the potential of these data science tools and became more engaged after we moved on to this part of the course.

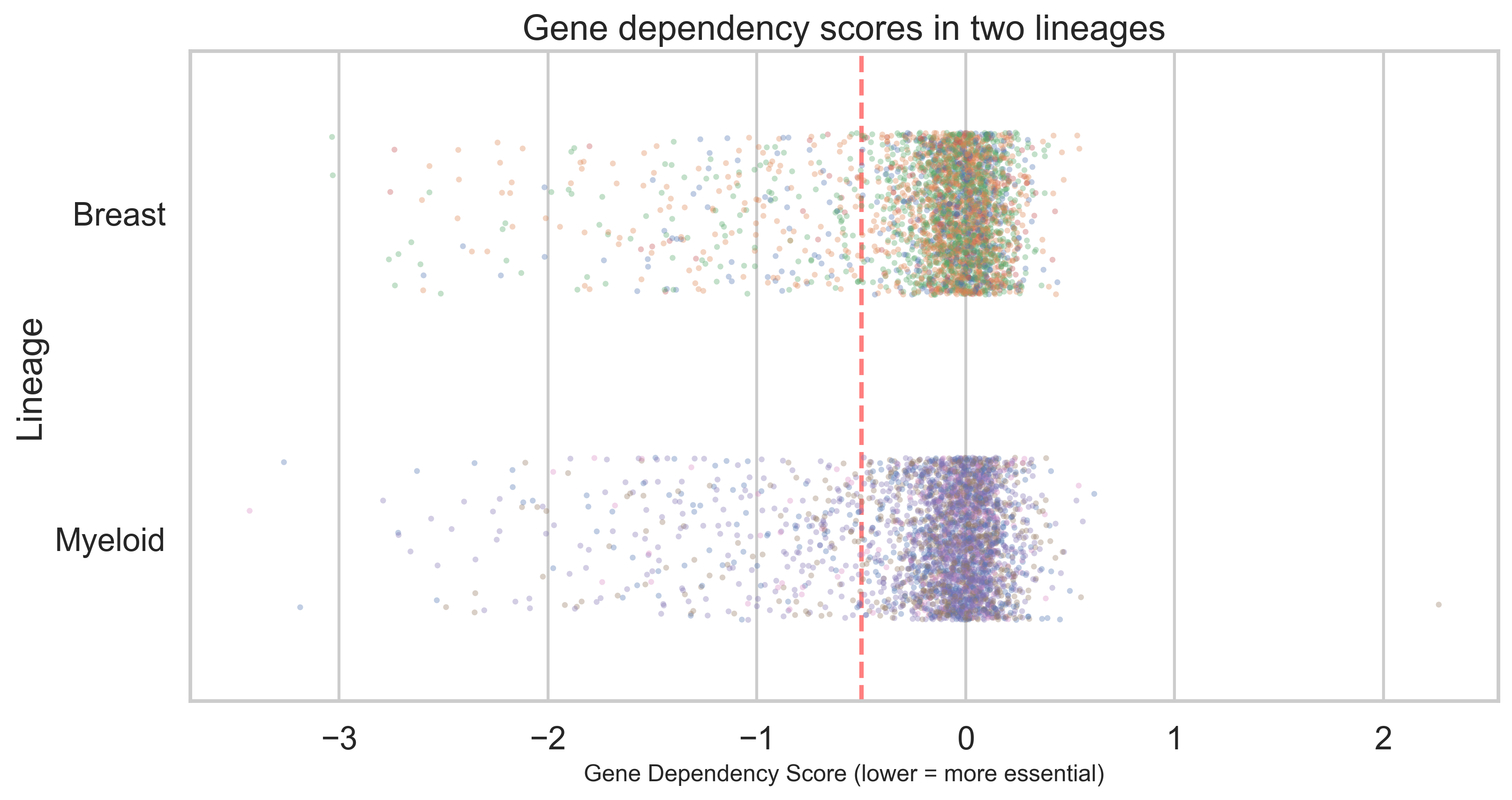

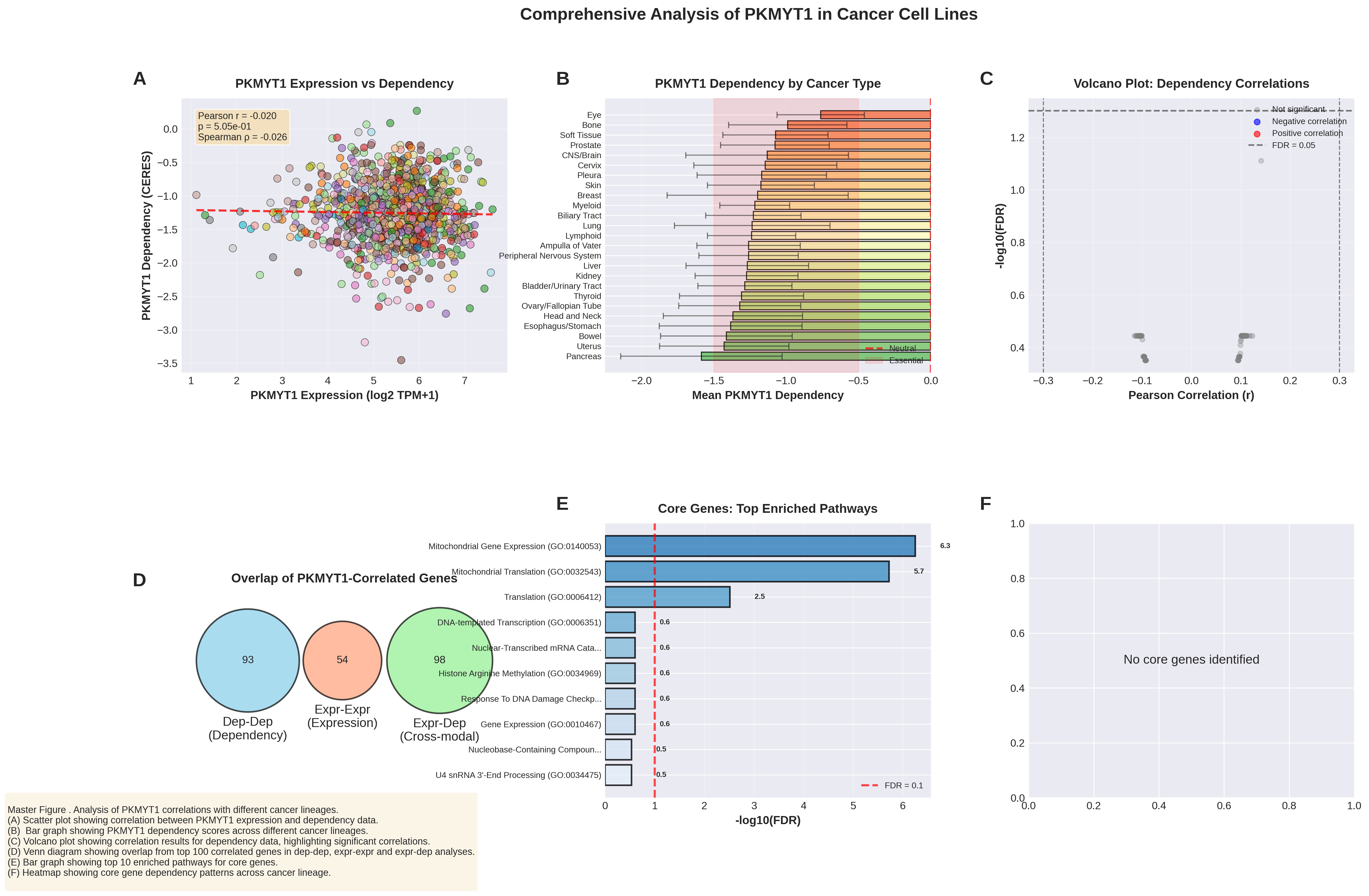

I chose a relatively complex data set, the DepMap gene dependency and gene expression data, that feature data for over 18,000 genes and over 100 cell lines. The individual datapoints signify loss of fitness following gene knock out, and level of expression per gene for a given cell line. The students in the class were a mix of biochemistry, neuroscience and ecology undergraduates, so gene dependency cancer data are not immediately relevant to many of them. However, DepMap data are an excellent example to work on correlation, regression and other advanced statistics. The dataset is large but manageable, and there is a clear biological interpretation: loss of fitness and gene expression levels. For the class work, I trimmed the data down to two cancer types: breast and myeloid cancer to keep the data volume manageable. This provided a valuable resource for teaching basic statistical analysis and data grouping, both of which are essential skills for working with data frames. From informal student feedback I received, I gather that this was a good choice of data that allowed for interesting exploration and had an immediate biological interpretation.

The obvious choice for dataframe analysis with Python is the pandas package. I was briefly considering teaching the more modern polars library (a Rust-based pandas alternative that is faster and allows lazy loading of large data sets). However, I decided that, at this stage, pandas remains the best entry-level package for working with dataframes and meets the needs of beginners who want to work with biological data.

In terms of data visualisation, there is a much larger selection to choose from in the Python ecosystem. Exposing the student to a larger variety of visualisation packages would just lead to confusion, so I decided to stick with matplotlib initially and expand to seaborn when moving towards more complex statistical analysis. The alternative would have been to go directly to Plotly or Altair, which provide a higher-level API. However, I think the basic syntax of figure generation provided by matplotlib is actually very useful to teach core techniques like understanding figure composition and axes hierarchy. This foundational knowledge makes learning higher-level packages later on much easier.

Advanced topics

Following this exploration of pandas and data visualisation, I planned to cover a few more advanced topics. My choice here was to use image processing with NumPy and scikit-image, and text analysis with generative AI. This would have made the course a more complete package that leaves the students with plenty of material to build on. Unfortunately, the scheduled lecture time was only 5 hours, and the lab time was devoted mainly to exercises and assignments. I'm still planning to develop material for these two subjects and expand the course to 8 lectures next year. In my opinion, going beyond the usual pandas/matplotlib data frame analysis would have given the students a much more solid grounding in different aspects of Python applications in bioinformatics. In particular, exploring programmatic access to LLMs and agentic AI is timely and feasible using one of the high-level SDKs available from OpenAI, for example.

Learning environments: from browser to local development

Students need to work with Python in different environments depending on their stage and goals. I introduced the progression as: browser-based Python for learning concepts, Google Colab for interactive data analysis, and eventually local development with the terminal and IDEs like VS Code for more ambitious projects.

Each environment has a role. Browser-based Python (using Pyodide, discussed below) removes all friction from getting started—students can write code within the lecture itself. Google Colab provides seamless access to the scientific Python ecosystem without installation overhead. Local development—managing virtual environments with tools like Astral's uv, working with version control, using a proper IDE—teaches the practices of professional programming. For students interested in building tools, automation, or contributing to open source, this final environment is essential.

The typical progression should be: start with the browser for fundamentals, move to Colab once comfortable with packages, then transition to local development for anything beyond data analysis notebooks. Some students may never need the last step. But for those who do, the transition should feel supported and intentional, not like an optional extra.

How to teach Python to biology undergrads

Course structure and learning aims

I inherited a course structure of 5 lectures and 10 labs. This seemed reasonable on paper, but it presented a real challenge: covering a lot of material in limited time. I front-loaded the first two lectures with the basics—variable assignment, lists, for loops, dictionaries, functions. Looking back, this was too dense. Students were overwhelmed by the abstraction. When I redesign the course, I'll spread these fundamentals across four lectures and slow down considerably.

The remaining three lectures shifted into applied work: pandas and data analysis using DepMap. I structured the assessments to reinforce this progression: a basic Python test covering the fundamentals (10% of marks), a sequence analysis assignment to probe those skills further (20%), and a major correlation analysis project—the capstone—accounting for 70% of marks. Students had three weeks for the sequence assignment and five weeks for the DepMap analysis.

Making material accessible via a website

When I started planning, my instinct was to design traditional lectures with slides. But immediately, I hit a wall: how do you meaningfully teach "what is a dictionary?" or "how do for loops work?" by talking about them in the abstract? It seemed impossibly tedious and disconnected from biology.

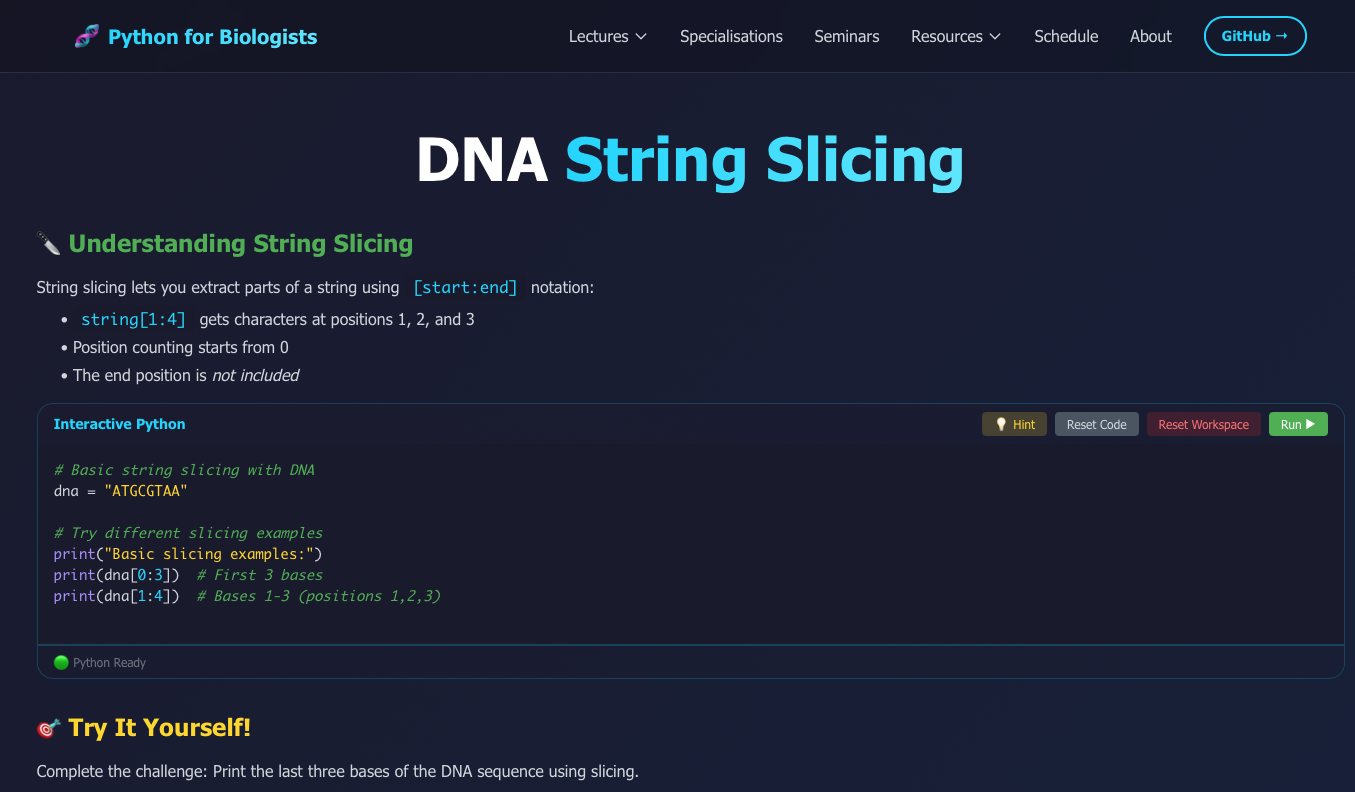

So I decided to do something different. I'd build a course website where students could interact with code directly during lectures. No installation, no setup barrier—just write code, run it, see what happens. This required learning web development, which felt daunting at first. But around the time I was planning, Claude Code became available, and that changed the calculation. Suddenly, building a custom learning platform felt feasible without months of work.

I chose TypeScript, React, and Next.js as my stack, designed a clean template using Tailwind CSS for consistency, and then—this was key—I could generate new material by prompting Claude with specific instructions for each slide or exercise. A few iterations, some testing, and new content was ready. This meant the development time stayed manageable, and I could focus on pedagogy rather than coding every detail myself.

Interactive material using Python in the browser, Google Colab and DataCamp Classroom

One of the key decisions was making basic concepts interactive. Until recently, this would have been impossible—browsers couldn't run Python. But Pyodide changed that. It's a framework that lets Python run directly in a web browser, safely contained, without any installation. Students can write code on the lecture website and execute it immediately.

This isn't just a convenience feature; it's pedagogically important. When students encounter "for loop" as an abstract concept, it's forgettable. When they write a for loop to iterate through DNA codons, hit run, and see it work—that's concrete. That's learning. In the current version of the course, I used Pyodide mainly for demonstrations, but I'm convinced I've only scratched the surface. Next year, I want to build in many more "stop and try it yourself" moments—students pausing to write code and testing their understanding in real time.

For larger exercises and practice, I moved students to Google Colab. It has the full scientific Python ecosystem available, and again, it requires no installation. This bypassed a huge barrier: students could move seamlessly from "I understand this concept" to "I can apply it to real data" without wrestling with terminal commands or package management.

I also integrated DataCamp Classroom, a self-study resource that emphasises hands-on learning in the browser—a similar philosophy to mine. Setting it up was straightforward (one email, a few forms), and their platform gave me useful engagement data. We had 239 hours of usage and a 39% completion rate. Students used it alongside the practice notebooks, especially during lab sessions where graduate students could guide them. I think it helped, particularly for students who needed extra scaffolding or wanted to revisit concepts.

The tooling adoption challenge

I introduced students to Python in the browser first, then colab notebooks. This lowers the barrier to entry considerably—anyone can start coding immediately. My intention was that students would eventually progress to local development, using the terminal to manage virtual environments with uv and coding in VS Code or Cursor.

In practice, this didn't happen. Only 5 of 60 students made the transition to local development.

Looking back, I think I underestimated how comfortable students became with Colab. Once they could run code, visualise data, and complete assignments without leaving the browser, the motivation to climb another learning curve disappeared. I provided materials and guidance, but I treated it as optional—an "advanced pathway for interested students" rather than something integral to their development.

This is partly defensible. For pure data analysis work—which is what most biology students do—Colab is genuinely sufficient. You don't need the terminal to analyse DepMap data or make publication-quality figures.

But partly, I think I made a mistake. The 5 students who did transition reported something I recognise from my own experience: once you get past the initial friction, everything changes. They could write scripts, automate workflows, manage projects properly, even start thinking about contributing to open source. These are powerful capabilities that Colab simply doesn't offer.

So next year, I'm making this different. Local development won't be optional. I'll dedicate lab sessions to hands-on work with the terminal, teach version control, and frame it not as "advanced" but as a different toolkit for different problems. Without this capability, I don't think many students will move on and develop their skills and build new projects with Python.

The AI problem

Here's where things got genuinely uncertain. I wanted students to reach a level where they could tackle ambitious projects—a real correlation analysis of the full DepMap dataset with 40+ individual tasks. But I knew they'd only have 5 weeks of Python fundamentals. Prior to AI, most students wouldn't have managed this challenge.

The availability of ChatGPT changed the equation. Students could now ask for help with code, iterate faster, and tackle complexity that would otherwise be out of reach. But this opened a new problem: how do you ensure students are learning with AI rather than outsourcing their thinking to it?

Surprisingly, most didn't seek out sophisticated agentic AI tools; instead, they used basic chatbots. But that was enough, and the majority completed the analysis. Ultimately, code quality and documentation were the primary criteria for marking, in addition to task completion. This forced students to engage with what they'd written, explain their choices, and, to some extent, understand their analysis.

Looking back at what students submitted and observing them work in labs, I believe they did genuinely try to understand and not just copy and paste code. They asked thoughtful biological questions, debugged their code when it failed, and revised their visualisations in response to feedback.

But I'd be naive not to acknowledge the uncertainty. Some code was probably entirely AI-generated. Some students may have understood the analysis conceptually without fully grasping the mechanics of the code. A traditional pen-and-paper exam would tell me definitively. It would ask students to predict code outputs, fix errors, and explain logic—all without AI assistance. That kind of exam has its own limitations, but it would answer the question: do they actually understand Python, or are they just fluent with ChatGPT?

That said, my clearest impression from labs was that students took the work seriously. They cared about understanding, not just completing. They recognised AI's limitations and wanted to be critical users. I think that's pretty reassuring.

Outlook

How did we actually perform? The data present a mixed picture that raises some concerns but also supports some of my assumptions. On the surface, the marks were higher than I expected: the initial Python test averaged 82%, and the final assignments had a median of 67%. These numbers suggest functional competence, but I have to be honest: this almost certainly reflects the "AI multiplier." Without ChatGPT, I suspect those figures, particularly for the complex DepMap project, would have been significantly lower. Is this a problem? It's complicated. The answer depends on what we're actually measuring.

According to the module evaluation survey (24 responses, 44% response rate), students rated the quality of teaching at 2.3 out of 4 (median 2), with overall satisfaction at 2.4 out of 4. These are not the numbers I was hoping for. The feedback was direct: the pace was a "sprint" when they needed a "jog," and the 70% DepMap project—which I estimated at 40 hours—clobbered them with 80+ hours of work. One student's comment really stuck with me: "I felt as if I was thrown in the deep end and was only learning stuff through external resources rather than the ones provided." That stings, but it's essential data. But the same survey tells a different story in other areas. Practical skills and career relevance were rated at 3.2 out of 4 (median 4), and understanding of how to use AI responsibly was rated at 3.4 out of 4 (median 4). Students struggled with the material and its delivery, but they recognised the value of the course. This tells me the "Innovation Tax" was high, but the "Innovation Dividend" was real. Students developed capabilities they found deeply valuable for their futures, even if the pathway I built for them was thorny. As one student put it: "I learnt a lot of practical skills... I have been able to visualise and learn to deeply interpret plots." That is the win I was looking for.

Interactive Evaluation Dashboard

Explore the full survey results, grade distributions, and feedback analysis

View Evaluation Data →So, where do we go from here? The design philosophy is sound: Biology students do engage when programming is grounded in real data and biological questions. Scaffolding from abstract concepts through pandas and into ambitious projects is the right arc. And yes, AI assistance at the capstone level allows students to reach further than they could alone.

Ultimately, did the students learn to understand and use Python deeply? Some almost certainly did. Others may have learned to work with AI-generated code without fully understanding the mechanics, but I'm confident that most students gained skills they'll actually use. They learned to think analytically about data, recognised the value of combining basic programming skills with AI assistance, and engaged with real, complex biological datasets.

Next year, I will slow the pace of the lectures and spread them across eight sessions rather than five, with more interactive examples. I'm also making local development integral rather than optional. I'm also considering adding a small invigilated exam to test genuine understanding, even if it's just 5-10% of the grade. The core approach, Python taught through biological application, scaffolded with interactive tools and supported by AI, still feels right for 2026.

Overall, we guided a cohort of beginners to a point at which they could navigate an 18,000-gene dataset and extract valuable information from it. I'm confident we moved the needle further than traditional programming education typically does. Our students didn't just "learn Python"; they learned to converse with data in a world where that conversation is increasingly mediated by AI.